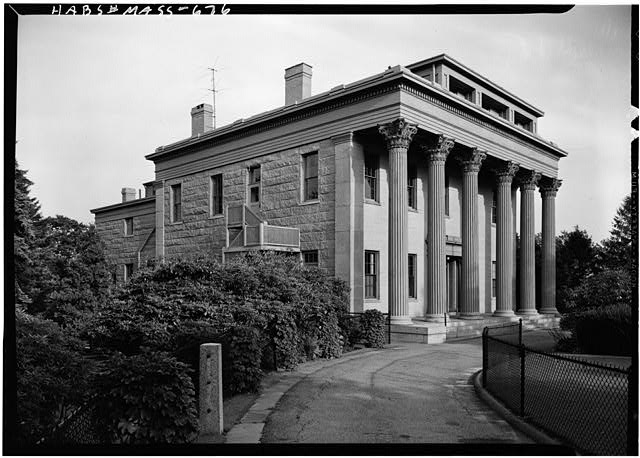

When the William R. Rodman House was built in 1833, it was one of the finest – and most expensive – homes in the country. Designed by Providence architect Russell Warren in the fashionable Greek Revival style, the massive home took advantage of its prominent location on County Street with six show-stopping Corinthian columns gracing the impressive front facade.

Hand carved and constructed in Providence, the ornate columns traveled by boat to the famed New Bedford wharves, then were transported to the building site. There, they have helped make the building an architectural landmark for nearly 200 years. But time has taken its toll on the columns. Roof leaks and animal infestation has sped up the deterioration, putting the columns in danger.

At the same time, the best use for the building has changed over time. The mansion has had many purposes over the years, from a single-family residence to a school building, then converted to commercial office condominiums in the 1980s. At that time, preservation restrictions were put in place, protecting the building from unsympathetic restorations or demolition.

Today the Rodman House is nearly empty, with the pandemic cementing work-from-home habits. The building may now be better suited for multi-family housing or another use, and will need to undergo restoration.

Time for a New Chapter

So what to do about those deteriorating columns? Who would take on the huge and expensive project of restoring the protected columns back to their original state? As it turns out, this endeavor was more difficult than imagined. Woodworking craftsmen are not as easy to find as they once were, let alone the materials to recreate two-story columns. What’s more, the replacement columns will need to stand the test of time, built in a way that will not require any significant maintenance for the foreseeable future. And finally – what will the preservation restrictions allow?

Fortunately, there has been increased flexibility regarding the use of new preservation technologies and materials in recent years. This has allowed for the use of materials like high density urethane (HDU), a “better than wood” material that is impervious to weather, pests and ultraviolet rays. Once painted, the new columns will be indistinguishable from the original columns.

But the final hurdle: how do you replicate the intricate details of the original columns? For AHF, the answer lies with a group of talented designers mixing modern technology and traditional craftsmanship.

AHF has taken on the replication of Column #6, the column that was in the worst state of deterioration. In partnership with the project architect, contractor and other preservation consultants, FORMA Beyond has been hired to reconstruct and replicate Column #6 using extensive 3D laser scanning to document existing conditions, and cutting-edge CNC machining techniques that will reproduce the column.

What does this all mean, exactly? I have to admit, before talking with the designers at FORMA Beyond, I only had a vague sense of how today’s technology played a role in historic restoration projects. I imagined high-tech tools scanning the artifact, and then someone pushing a button and… POOF! A 3-D printer (or something) would just create the new version. It would just….construct it. So, I am here to tell you, I was wrong. (Obviously). I learned so much talking with the FORMA Beyond designers that I have included our conversation below.

Q&A with FORMA Beyond’s Justin Blanchard, Director of Design and Operations and Steven Weber, Product Designer / Project Manager

The interview has been condensed for clarity and length.

How did you get started doing this kind of work?

Justin: Brian Keane is the owner of Bay Contracting out of Waltham, MA. They are general contractors, but they are also known for heavy duty waterproofing and restoration. So they do a lot of masonry and brickwork on brownstones and all over Boston. I have a background in the trades – my father was a carpenter, my brother-in-law is an electrician, and I went to trade school for electrical, sort of an all around handy guy. Then I went to UMass Lowell for sculpture.

I started working for Brian to help make forms – things like window sills and door lintels. Then we began to cast our own concrete for some of his jobs. And from there, I started molding more and more complicated things. My first big challenge was at Bridgewater Academy, where we replicated the exterior columns.

I got a bunch of broken wooden pieces and had to put it all together with clay, and then make rubber molds. We cast some concrete and gypsum parts to replicate the original. Once we had done that, it was kind of “game on.”

Eventually we got a CNC machine and started being able to carve bigger and more elaborate things. Now I have two CNC machines and we’ve got a full paint booth.

Brian knew that we could just take on anything that is unique and requires that kind of skill, so from there we formed FORMA Beyond. The clients rolled in, asking for more and more complicated things, and we just kept taking them on.

You do both restoration work and make new sculptural elements – what is your favorite kind of project to work on?

Justin: We keep trying different things, but we seem to always come back to restoration. It’s my passion – I get to help take part in American history, keeping the integrity of a true sculptor. There’s no one doing it like they used to, it’s kind of a lost art. I’m using modern technology to do it, but there is a lot of that hands-on work that I love.

I will say that the modern, stand-alone originals are really, really cool to work on. But as cool as they are, they won’t be there for 100, 200 years. And I don’t get to drive around and point at buildings with my son and say “this is something I did”.

How do you start a big project like this?

We started with the photographs, but then I finally got the pieces from one of the capitals here in my shop. There’s a thick layer of paint that we stripped off a couple of them, but we can see the original tool marks of the chisels.

To see how they built it helps me in remaking it – you can see where they had to split this into an octagon to create this round piece. I have the ability to do different things because of the machinery we have now, but sometimes I realize they really had it figured out. Their method is still the best method.

So, first you create a 3D scan, then the software speaks to the CNC machine, is that right?

Right. The more complex the shape, the more we need to clean it up. First in the software, and then cutting it on the machine, and then hand sculpting.

Steven: The machines are great, but you can’t overload them with organic. They can cut geometry all day long, but what the machine is trying to do is take an organic design and give it geometry. I’m sure there are others who can do it, but I find it faster to recreate it by hand.

Justin: We carved this out of a bunch of thin layers so that we could get as much of that undercutting as possible, then we glued it all together by hand. When parts are missing, when details are washed out – I have to make them up with Bondo and sculpting. Then we do it again to get all that detail. We need that final file to be as close to done as possible.

I think of the CNC machine as another laborer. If I give the CNC bad information, it’s going to produce a bad product, but it can only do what I can tell it to do. So we took the first scan, which had all the paint on it. We had the machine cut it out, so now I have something physical.

Steven: We shape it more by hand, we re-scan it now that the machine’s like, oh, I can do a better job. It spits out another one, but it’s still not perfect. It’s closer, but now I can tool it again, make it even closer, scan it again. Now the machine can give us a 90% match. And we can fix that last 10% by hand. There’s a lot of back and forth to getting the final product where we’re happy.

I feel like this is a shift in the way that I’ve been thinking about this. I think I kind of went into this thinking that you guys were using technology, like you were tech geniuses, you were pressing buttons, making things happen and then pushing a button. But now I see that what you’re doing is so much more similar to what the original craftsmen did just with new technology guiding you, and with different materials. But other than that, it’s the same thing.

Steven: What the technology allows us to do is not have to sculpt this one part to this level on all six columns. If AHF wants to do five more columns, we’ve done the leg work up front to get to this point in the software. We’ve scanned it, we’ve cut it, we’ve shaped it, scanned it again, cut it again, we shaped it again. So now we’re able to cut something that’s pretty close.

I’m not going to underplay it – there’s a lot of labor. There is a significant amount of the time spent. This one section took a month to get it to a point where it can be replicated.

This is such an interesting mix of technology, art, sculpture, trade knowledge. What do you call yourselves?

Justin: We are makers. Steven is my lead designer. Typically I say architectural design, but that sounds like I’m an architect. So now we say we design architectural elements. Desks, 3D forms, that sort of thing. One of my old employees, Carlos, used to say this all the time: “If they don’t make it, we fabricate it.”

How do you feel that this technology is changing the future of preservation or restoration work?

Justin: I think it can help keep it more accurate. We can get a drawing from an architect and from the photos, I can tell they made a mistake. The technology catches that mistake immediately. It’s the small details, I think, that could get lost in translation.

Are you worried that technology will replace your skills?

Steven: I think a lot of people have the mindset that just because technology is so advanced that it will wipe out jobs or minimize the effort of a human. It’s easy to assume that because we have a 3D scanner, we don’t need a lot of labor, but in reality, it’s just its tool. It’s another tool for precision.

It excites me to see this technology grow because it’s only going to get better and it helps so much. It really improves the level of detail we can provide.

Do you walk around the world and just see things that you want to fix?

Justin: It’s a curse, I think. Even before getting into any of this, growing up with a father who is a carpenter, you go into someone’s house and you notice a little gap, and you think “oh, they could have fixed that.” Now everywhere you look, and you start to question everything and wonder “what is that made out of”?

Do you have a dream building that you would love to get your hands on?

Justin: I don’t have a specific one, I just love doing work in New England because it’s all so historic. I was working on a building in Boston, standing on scaffolding at the top of the building and I can see Fenway Park, it’s the next block over, it’s right there. So I would never say, I want to work on that building someday, but being there was very cool. Anything with real historic value is so interesting to me.

AHF is excited to share that the new column was successfully installed and painted in April of 2025. Thank you to FORMA Beyond, Dan Whitaker from Whitaker and Sons, Michael Viveiros and Tami Hughes from DBVW Architects, and to the City of New Bedford for support from their Facade Improvement grant program.